Fred Schodt, Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics (1983), Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga (1996).

I’ve had these two books lying around for quite some time now, and it seems like now would be a good time to break my trend of posting reviews of things that the majority of this blog’s audience can neither read nor purchase easily. First up is Manga! Manga!. The book is broken into a number of sections, each with a fairly concrete subject, such as the origins of manga, themes in boys’ and girls’ manga, the industry, the future of manga, and a few more things in between, all in a little under 160 pages. You might think that this would result in a fairly scattershot approach to the monolithic subject of everything manga, but we end up with a fairly concise but focused set of essays that would be a good introduction to the subject. The book’s second half is devoted to English translations of four comics, Osamu Tezuka’s Phoenix, Reiji Matsumoto’s Ghost Warrior, Riyoko Ikeda’s Rose of Versailles, and Keiji Nakazawa’s Barefoot Gen.

Well, a good introduction other than the fact that the book is 25 years old. This isn’t exactly a fair criticism, but while the book may have been very poignant at the time, a lot of the ideas floating around in Manga! Manga! didn’t age terribly well, since the American landscape for the stuff was totally different, as the second-to-last paragraph makes it clear – “Most Japanese comics are unlikely to cross the cultural barrier between East and West in their original format. Those that do will probably be select classics with universal themes or works specifically created with Western audiences in mind. They are unlikely to become as common or as dominant as American comics once were.” Also, the whole bubble bursting thing took the idea of “JAPAN TAKING OVER THE WORLD” out of everyone’s heads right quick. Can’t win ’em all, I guess. Despite the disconnect between then and now, there’s still a fair bit of useful information in here, especially when Schodt takes a look at the industry or recent history of the format. Of course, a bit of this is presented as totally alien stuff (as it ought to have been), but between Schodt’s access to Tezuka and the Japanese industry at the time makes for at least a few chunks of very good reading.

Of course, that isn’t to say that I can unequivocally accept everything he presents here. Within a handful of pages, I saw the first claim that made the Japanese studies undergrad in me squirm – that one reason for the dominance of comics in Japan is Japanese kanji, making an ideogram -> pictures -> comics!! connection, an idea that would earn me a mountain of red ink and a referral to this book by a college professor or two. I had similar reservations about his ideas that manga can be traced back as far as 12th century scrolls and (probably unfairly) his sections on samurai and honor influencing more modern-themed works like Golgo 13. (gotta get back to the duke. always gotta get back to the duke.) Actually, Henry Smith does a much better job of pointing this out in his review of the book in Vol 10 #2 of the Journal of Japanese Studies, which you should just read instead of this part of this blog post if you have jstor access. Too bad I told you that now, since I’m just about to wrap up! (It’s not too late to see Smith bust out his otaku cred by talking about gekiga and his Garo collection in the article, though!)

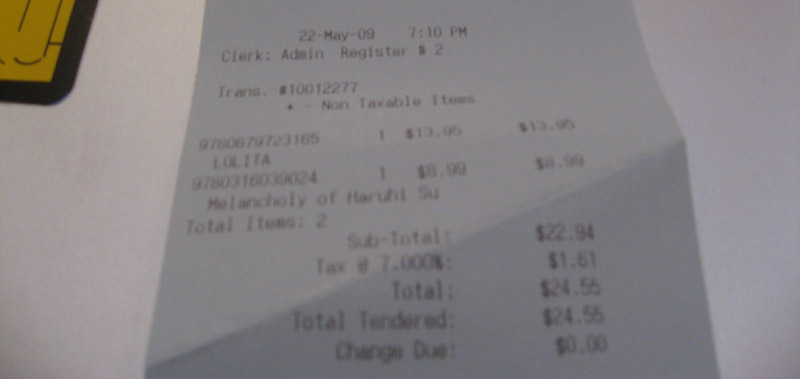

Overall, I’m not all too sure who to recommend this to. I mean, these days we have things like the internet to tell us about manga history, while a good portion of the rest of the book is either outdated or clashes too strongly with my ingrained ideologies for me to appreciate. Not to mention that the only people who I would have the opportunity to recommend the book to would have probably learned a lot of the stuff in here through it being dispersed into general nerd knowledge over the past 25 years. At the same time, it’s a fairly engrossing read, and actually has a fair bit of authority behind bits of it. (Which is to say I enjoyed it a lot more than Samurai from Outer Space which I will not rag on but will simply say that the most I learned from it was that someone out there with a Stanford education actually took Crystal Triangle seriously.) I’d certainly buy it at the $5 Amazon price if you had the bookshelf space, especially if you want a hard copy of something to cite, and I wouldn’t tell someone not to borrow and read it if their local library had it, but I’d suggest reading it with a grain of salt.

On the other hand, there’s Dreamland Japan, which will get a much shorter review from me because I love it so much that I will not write a single bad word about it. Also, I need to sleep soon. Where Manga! Manga! had things like opinion and theory (which I inexplicably hate all of the time especially when it comes from jerks like me), this sucker has big chunks of information to jam-pack your tiny otaku brains with. The first two chapters start off with a overview of the medium as well as its discontents (otaku, comiket, aum cultists). Schodt then moves on to an overview of a fair number of popular manga anthologies of the time, including demograpic and circulation information in handy little boxes. While some of the information is, unsurprisingly, a bit dated, a lot of the information holds up while also giving a pretty clear, in-depth snapshot of the state of the Japanese industry at the time.

This alone would make it worth a purchase, especially at the dirt-cheap prices that you can find it online, but then we get a hundred-page chapter that focuses on various manga artists of note. Schodt’s writing keeps things fresh as he profiles (and includes samples!) of one artist after the next, leaving a host of dogeared pages in any underinformed reader’s (my) copy of the book with mental notes to check the artists out once you’re done with the book. The next chapter is about Tezuka, and to be honest, I just thumbed through the chapter since nearly all of it was included in Schodt’s later Astro Boy Essays, which AWO’s Daryl Surat did a nice little review of in Otaku USA. (spoilers: you should buy it.) The final two chapters are on the future of manga, first in Japan, then in America. Again, being ten years old on a subject that’s constantly experiencing an incredible amount of change hurts these chapters’ relevancy a little, but they still provide a great picture of what was going on at a time that we can’t easily hop online and pull up websites about. Also, you get to see an absolutely ancient picture of the absolutely ancient Anipike, which should bring a smile to any old codger’s heart. So yeah, I would strongly suggest anyone interested in the history of manga or just manga in general pick up Dreamland Japan. It is both an engrossing read and will probably make you more informed about Japanese cartoons, an important trait of every educated citizen of the world!