Japanese Lecture/Blog Post Translation: The Space Between Anime and Manga: #4: Why is the Manga Version of Nausicaa So Hard to Read? by Takekuma Kentaro

Translator/blogger’s Introduction: This is another post in what will hopefully be a more regular series of translations of articles by Japanese bloggers and thinkers on manga, anime, and all of those sorts of visual culture that we enjoy so much. There’s a huge amount of interesting material available out there that’s quite unfortunately out of reach to a large part of non-Japanese fandom, and I hope that these posts help out in building the bridge between the English and Japanese-speaking ‘spheres. I was delighted to see a positive response to my first translation, a post by Tamagomago-san on the 3rd opening of Goku Zetsubou Sensei, and would like to thank everyone who commented on the errors in my translation. Again, if you notice any errors in my translation or if you have any comments/questions on this post, I appreciate every single one.

On to the article. This post is a translation of a post by Takekuma Kentaro (probably best known in the states for co-authoring Even a Monkey can Draw Manga) on his blog Takekuma Memo. This post (split in two parts, part 1 and part 2) was taken from the detailed handout given at one of his series of lectures at Kyoto Seika University with the collective title “The Space Between Anime and Manga,” and the subtitle of this specific lecture was “Why is the Manga Version of ‘Nausicaa’ So Hard to Read?” I was lucky enough to be able to attend this lecture, as well as the final two lectures in the series, which I hope to translate in the near future. I was also fortunate enough to obtain permission from Takekuma-sensei to translate his post, an allowance I am very grateful for. Some notes about formatting: I’ve tried to preserve the original formatting in a form that wouldn’t result in mojibake the average person’s browser, so I’ve gone with *s for circles and indents for arrows, both markers of the flow of the lecture in the original handout. Also, please keep in mind that this is a translation of a handout, and thus may require some level of independent thought in order to figure out what the author is getting at. Once again, I appreciate any and all comments, so please feel free. Happy reading!

– – – – – – – – – –

The Space Between Anime and Manga

Outline for the lecture series given at Kyoto Seika University

#4: Why is the Manga Version of Nausicaa So Hard to Read?

Lecturer: Kentaro TAKEKUMA

[A] The Complex Relationship Between Osamu TEZUKA and Hayao MIYAZAKI.

* Many publications ran memorial features on Osamu TEZUKA upon his death in 1989, and while most experts and insiders would memorialize him in these articles, Hayao MIYAZAKI, while acknowledging Tezuka’s achievements as a manga author, criticized him harshly with regards to his activities within the field of animation, leaving many around the world dumbfounded.

“But as far as animation—I say this believing that on this topic alone I have the right, and also some duty to say this—Everything that Tezuka-san had spoken about or advocated was wrong.†(“Tezuka Osamu ni ‘Kami no Te’ wo Mita Toki, Boku wa Kare to Ketsubetsu shita â€. Miyazaki, Hayao. Comicbox, May 1989)

Miyazaki sharply criticized Tezuka by saying that he believed that as an animator, Tezuka was a “Novice†and an “Unskilled Enthusiastâ€, but that despite this he was able to use his fame as a manga author to create his own anime company which then began to produce television anime, severely warping the direction of the Japanese animation industry.

On the other hand, Miyazaki also admitted that he once admired Tezuka as a manga author and had hoped to become a manga author himself. Thus, one can see that some elements of Miyazaki’s ambivalence about Tezuka are very deep-rooted. As for Tezuka, despite being an individual who held strong rivalries towards other authors, surprisingly, he never said anything in public about Miyazaki.

Anime historian Nobuyuki TSUGATA writes in detail about this matter in his books Nihon Animeeshon no Chikara (The Power of Japanese Animation) and Anime Sakka toshite no Tezuka Osamu (Tezuka Osamu, the Anime Creator) (both published by NTT.) Based on information he gathered through individuals who knew Tezuka personally, Tsugata reasons that Tezuka’s silence was caused by an over-awareness of Miyazaki. Tsugata bases this on the idea introduced by Kei ISHIZAKA that Miyazaki, with Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind (Kaze no Tani no Nausicaa), had accomplished what Tezuka had wished to do with anime. That is, Miyazaki created a masterful feature-length animated film which had both a grand story as well as grand themes similar to what Tezuka had successfully created in his manga, and shocked Tezuka by doing it first.

[B] His Early Days of Trying to Become a Manga Artist

* Hayao Miyazaki was born in 1941 (Showa 16) in Tokyo. His father was an executive in the aerospace industry, and he was born into an affluent family where he could be exposed to manga and other stories from a young age. Similar to Osamu Tezuka, born in 1928 (Showa 3), he was blessed with an upbringing that would allow him to immerse himself in his interests and hobbies.

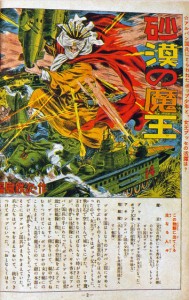

Fukushima Tetsuji’s “Sabaku no Maoh (The Devil of the Desert)” (1949-1956)

Fukushima Tetsuji’s “Sabaku no Maoh.” Miyazaki was in love with this illustrated story (e-monogatari) during his youth. The “Levitation Stone” in Laputa was based upon a similar item in this story.

Miyazaki was a Tezuka fan, and later wrote in an essay that during his high school years, he lost faith in his own talent as a manga author and burned all of the manga he had drawn up to that point. He says that he realized that if he simply copied Tezuka, he would never be able to become a better manga author than him. (Nihon Eiga no Genzai, Iwanami Shoten)

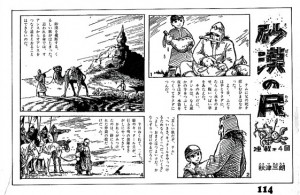

The illustrated story that Miyazaki seralized under the pen name Akitsu Saburo during his days at Toei Doga, “Sabaku no Tami” (The Desert Tribe). (1969-1970.)

After Miyazaki became an animator, he serialized one manga, “Sabaku no Tami,” under the pen name Akitsu Saburo for Shonen Shojo Shinbun (Boys’ and Girls’ Newspaper), published by Akahata (the newspaper of the Japanese Communist Party). Though this does have some (manga-style) defined panels, this is an illustrated story, and acts as both an homage to “Sabaku no Maoh” as well as a prototype for The Journey of Shuna (Shuna no Tabi) and Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind.

The illustrated story (“e-monogatari”) is a medium that was very popular after the war, but is now a nearly lost art. Art and story are written by the same individual, but unlike manga, the words and pictures are clearly separated. This medium cannot be ignored when thinking about Miyazaki’s manga.

[C] The Newly Recruited Animator with Directorial Aspirations

* In 1958, Miyazaki saw the Toei Doga film The Tale of the White Serpent (Hakuja-den), Japan’s first color feature-length animated movie, and decided to become an animator. After being hired by Toei, he discovered the Soviet production The Snow Queen as well as the French The King and the Mockingbird, and realized that styles of animation other than the Disney style existed. Here he met director Isao TAKAHATA and animators Yasuji MORI and Yasuo OOTSUKA, all of whom strongly motivated him.

Miyazaki worked on Gulliver’s Travels Beyond the Moon (Garibaa no Uchuu Ryokou, dir Yoshio KURODA) in 1965, soon after entering the company. While he was responsible for the in-between animation for the film’s final scene, he made strong suggestions to key animator Shun NAGASAWA and the film’s director Kuroda, and eventually the ending of the film was changed. In this new ending, Gulliver and the protagonist Ted, while visiting the Robot Planet, discover that inside the cracked body of the Robot Princess lives a human princess.

It’s hard to figure out what would make the director accept such a major reversal of the story that had been planned up until that point. While it would not be unusual for an animator to be fired over an incident like this, Miyazaki on the other hand managed to have his changes accepted by the project’s core staff. From this incident, we can see that his skill overwhelmed those around him, even from his earliest days as an animator, and that even in these days he had strong directorial aspirations.

While working voluntarily on Isao Takahata’s directorial debut Hols, Prince of the Sun (Taiyou no Ouji Horusu no Daibouken), Miyazaki offered a huge number of setting illustrations, and was credited with the position of “scene design” in the film, a title that was newly created specifically for his work in the film. Essentially taking the position of “animation producer” in the place of Takahata, who could not draw, one could call Hols the starting point of Miyazaki’s career.

* Miyazaki begins freelancing in 1971, and together with Takahata who had recently left Toei after taking the responsibility for Hols‘s poor box office performance, he turns his endeavors to television anime such as Lupin III and Heidi, Girl of the Alps (Alps no Shoujo Haiji).

[D]His Discouraging Directorial Premiere and the Trying Days that Followed

* Miyazaki directed his first television anime, Future Boy Conan (Mirai Shounen Konan) in 1978, and his first animated film, Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro (Lupin III Kariosutoro no Shiro) in 1979. While this film is considered a masterpiece today, it did not perform well financially at the time, and he was unable to create an anime film for several years afterwards.

During this period, he worked on the second season of the Lupin III television series, and in the final episode, “Saraba, Itoshiki Rupan yo” (“Farewell, Dear Lupin,”) he bases a number of scenes on the Fleischer Brothers’ Superman series, paying homage to an animation series he had seen as a child.

During this difficult period for Miyazaki, he creates a draft for a work called Mononoke Hime (a different work from the film he later created) as well as a large number of setting boards and other materials for Totoro. This is a textbook example of one’s direction in life being determined by what they do during times of adversity.

[E]: Miyazaki’s Turning Point: Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind’s Manga Serialization and Anime Adaptation

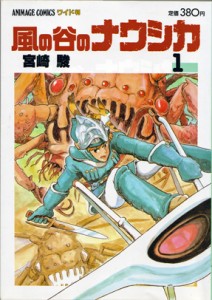

Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind’s first volume, Tokuma Shoten.

*The event that began Miyazaki’s climb out of this difficult period was his meeting the Animage editor Toshio SUZUKI. Suzuki asked Miyazaki, “If you can’t make anime, then please draw manga.â€

Miyazaki, having not drawn pictures with a pen for over ten years since making “Sabaku no Tami†(Miyazaki’s keyframes and imageboards were mostly done in pencil and light paint) expressed his anxiety about this fact to Suzuki, who replied, “We can print your manga even if it’s drawn in pencil.â€

At this point, Suzuki thinks that if the manga does well, then it could open the door to an anime adaptation which he could have Miyazaki direct.

Suzuki’s expectations were on target, and the Nausicaa manga performed well, which led to plans for an anime adaptation. According to the accounts of those working on Nausicaa at the time, Miyazaki, who had received another chance, and possibly his last chance, to direct an anime, furiously devoted himself to his work like a man with nothing left to lose.

Miyazaki put the Nausicaa manga on hiatus to focus on anime production, and though he resumed the manga during later stages of anime production, the manga of Nausicaa took a full 12 years to complete, beginning serialization in 1982 and ending in 1994.

In the end, Miyazaki, a man who is foremost thought of as an animator, takes an opposite stance in this matter from the man he admired, Osamu Tezuka. Tezuka, who since his young days wished to create anime, first became successful as a manga author, then used his position as a manga author to create anime productions. However, Tezuka, unlike Miyazaki Hayao or Katsuhiro OOTOMO, could never completely stop creating manga in order to focus wholly on anime production. That Tezuka, the man who revolutionized story manga, ended his career as an anime creator as a man who was never particularly considered remarkable could be due to the fact that he could never quit his “side business†of being a manga author.

Part 2

[F] On the Nausicaa Manga Being “Hard to Readâ€

* These days, the manga version of Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind is established as a masterpiece of story manga. The themes and setting of Nausicaa are strongly influenced by the American author Frank Herbert’s ecological science-fiction masterpiece Dune. Dune shocked readers at the time with its detailed description of a distant planet, describing aspects of the planet from its culture and history to even its geography and ecosystem, constructing an entire detailed fictional world. Not to be outdone by Herbert, Miyazaki created a similarly detailed world in Nausicaa, except through the visual medium of manga.

As the story progresses, more and more of Miyazaki’s speculative thoughts and political beliefs, as well as his contrasting despair and hopes for mankind, were tackled head-on, creating a masterwork that displayed much of Miyazaki’s “core†as an author. The manga’s early themes of utopian socialism and idealism based upon environmentalist beliefs changed during the manga’s 12-year serialization, ending in what can only be called an acrobatic performance, leaping from thoughts of despair to ones of hope for human civilization. As a story manga, it is a work whose grand plot rivals that of Tezuka’s Phoenix (Hi no Tori.)

When looking through Miyazaki’s oeuvre, the Nausicaa manga has more themes in common with his later Princess Mononoke (Mononoke Hime) than its anime adaptation. Though Princess Mononoke is even called “Nausicaa Part 2†by fans and critics, I feel that it tries to fit too many subjects and themes into its 2 hour and 15 minute running time, and while it was highly commercially successful, that as a work of film, it was difficult to digest everything that it presented.

* Incidentally, when I first read the Nausicaa manga in 1982, I was left speechless by its themes and the level of detail of its world, but at the same time, I was surprised at how “hard to read†it was. Of course, this is a subjective opinion, and I believe that how hard or easy a certain work is to read depends on the reader. However, I feel that must be at least some who share my view.

[G] Why I Feel Nausicaa is “Hard to Readâ€

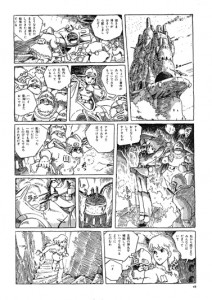

Page 48 from volume 1 of Nausicaa, released in 1983 (serialization began in 1982). Each individual panel is too complete, and the characters and background are drawn with lines of equal thickness. This leads to the characters not standing out. While as a work of illustration, it is of extremely high quality, that and the difficulty of a given manga to read are two separate subjects.

(1): Though this is in some part the fault of the manga being drawn in pencil, the characters aren’t drawn in distinct “heavy lines.†The standard theory when creating manga states that one should draw characters with thick, defined lines (heavy lines), and the background with a thin pen such as a mapping pen, causing the characters to stand out from the backgrounds. Drawing the characters and backgrounds with the same quality of line, (often even leaving no space between the two) the characters often seem to get buried in the background.

2: The individual panels are too “complete†as illustrations. This is only true for each singular frame (panel), and there isn’t enough of an attempt to connect one frame to the next, or to guide the reader in following the flow of the manga.

3: The characters’ faces are roughly the same size in every panel. Nausicaa utilizes many different kinds of panels, vertical, horizontal, oblique, large, small, and so on. This is not too different from the average manga, but the problem lies in the fact that the size of the characters in each panel stays roughly the same, meaning there is little variation in the scale of each panel. Nausicaa’s large panels do not feature characters, but rather depict finely detailed depictions of scenery.

Taking this into consideration, one must conclude that, as a character-driven story manga, Nausicaa uses very few techniques that draw the reader’s eye to its characters.

However, this work is a human drama that aims to depict the relations between its various characters. For that reason, the objectives of the narrative and the content and composition of the manga’s images do not match up.

This discord that we see in the Nausicaa manga is not present in any way in Nausicaa the anime. (In the anime, the characters stand out as you would expect them to.)

* Film is shaped through the control of each scene’s length via the process of editing. In contrast, manga controls “time†through arranging the layout of the pages for the reader. This process is what we call “panel layout.â€

Manga is different from film (anime) in that one cannot directly control time. Through the differing layout, shape, and size of each panel, one can guide the reader’s gaze, and create a false sense of time. When reading the early volumes of Nausicaa, one can see Miyazaki struggling to transfer filmic “time†to manga “time†within the organization of the panels, an aspect of these volumes which I find very interesting.

The technical irregularities seen in the Nausicaa manga are faults often seen when animators or illustrators unfamiliar with panel layout try to create manga. What happens with these individuals’ manga is that the composition of each individual frame is too complete.

Page 196 of the final volume, released in 1995. In the middle of the long side-to-side panel four rows from the top, there is a close-up of Nausicaa’s face. The background in this panel is simply a concentration of straight lines, forcefully drawing the reader’s attention to Nausicaa’s face. Panel composition like this is rare in the earlier volumes of Nausicaa. It’s possible to argue that through the course of the manga’s serialization, Miyazaki understood how to layout manga panels.

However, regarding Nausicaa’s seventh volume, released twelve years after volume one, I would like to note that the panel composition becomes remarkably easier to read. The flow from panel to panel becomes more natural, and its characters become far easier to identify when flipping from page to page, as the scale which the characters are depicted is effectively varied. One of Tezuka Osamu’s great accomplishments was his ability to naturally guide the reader’s gaze through the panels of his stories, and in the end, Miyazaki seems to have been able to master this skill as well.

[H] How the Image is Treated in Miyazaki’s Anime

* Putting manga aside and looking at Miyazaki’s “main business,†animation, we enter a medium in which Miyazaki has been a master of since his earliest days. Usually the first topic to come up when talking about Miyazaki’s anime is the mental ease and pleasure that comes with watching his films, a result of the works’ editing and pacing.

Good examples of this are the escape scenes from the triangle tower in Future Boy Conan (where Conan escapes with the robots, then where he falls from the tower while holding Lana in his arms). In both of these scenes, Miyazaki’s techniques challenge our common expectations of the standard escape sequence which we have come to anticipate in popcorn entertainment, while also acting as exciting scenes on their own.

* Another trait common to Miyazaki’s anime is the extraordinary sense of his “treatment of pictorial space.†I once tried my hand at interviewing Miyazaki, and a thing that struck me was the strength of his desire for his viewers to be able to personally feel a sense of “space†in the worlds that he creates. For Miyazaki, whether it is live-action or animated film, conveying “a sense of space†to the viewer is a serious and difficult task.

Miyazaki brought up a Japanese film, Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, as a good example of a film that illustrates the importance of this sort of space. In the middle of the main street of the film’s town is a watchtower, and two of the city’s powers confront each other, one on each side of the tower. The main character, a ronin played by Toshirou MIFUNE, supports neither side, and climbs the tower to spectate the encounter from a bird’s eye view.

“But you know, as the film proceeds, the audience stops being able to tell which side is which.†Miyazaki said. He went on to say that viewing the two forces “from a flattened perspective causes a sense of confusion.†But, in the manga of Nausicaa, the relative positions and distance between of the Valley of the Wind and Tolmekia never seem clear to the reader, despite Miyazaki going so far as to include maps to help them in this regard. Hearing Miyazaki, who had such difficulty conveying this sense of space in the manga, talk about his fixation on the audience’s “sense of space†surprised me.

Miyazaki pays a lot of attention in his own works to the acts of rising and falling. On the topic of vertical movement as opposed to movement on a flat plane, Miyazaki said “the viewer intuitively understands the acts of climbing and falling.†“Film is the depiction of motion and movement, and the forms of movement that are most intuitive to a viewer are falling and flying.â€

The level of attention Miyazaki pays to the physiological response of his viewers must surely be one of the reasons that he has risen to such a prominent position as an entertainer. I know of no other filmmakers who so thoroughly work with the “space†of their settings and the “movement†of their characters.

[I] Miyazaki’s Anime as Slaves to Depiction

* Tezuka Osamu is an author of stories. To put it very bluntly, he always works towards the goal of “allowing the reader to understand the story.†Thus, the way I see Tezuka’s works, the artwork and characters are “slaves to the story.â€

* Takahata Isao is a Slave to Production. Takahata, unable to draw, strives to create drama between his characters through his direction. Hilda, from Hols, Prince of the Sun is at once a human girl and the younger sister of a demon. Her human side and demon side are constantly in inner turmoil. How does one depict a character constantly undergoing this difficult personal struggle? In pondering this question, Takahata discovered that such a person would simply remain expressionless.

In order to depict the fierce inner struggle of an expressionless character, directorial strength, not pictorial strength, is more important.

* Miyazaki Hayao is a Slave to Depiction. Miyazaki has the ability to take a scene which would look boring if read on paper and turn it into a grand spectacle. A good example of this would be the opening scene of My Neighbor Totoro (Tonari no Totoro), where he devotes a full ten minutes to a sequence in which Satsuki and Mei move to their new house.

How many other filmmakers on this planet exist who would spend this much time dragging out a scene which gives background information to the rest of the film and little else? The viewers explore the house alongside Satsuki and Mei, and in the process fully understand the “space†of their new house. At the same time, we gain a sense of empathy for the characters and are drawn into their world. (I imagine that had Tezuka or Takahata directed this scene, it would have been wrapped up in all of thirty to sixty seconds.)

Another scene that could only have been created by Miyazaki is the sequence in Spirited Away (Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi) where a sludge-like monster comes in to take a bath. The charm of this scene would be difficult to describe in a planning document or a script, but Miyazaki, the animator-turned-director, was able to create this scene without having to subject it to a production process that involved the written word. This is an ability that only a very specific kind of director holds.