Manga Criticism Translation: “At First, I Wanted to be a Manga-ka”: Analyzing the Nausicaa Manga by Kumi Kaoru, pt 1

Wednesday, November 4th, 2009Translator’s/bloggers introduction: Some time ago, I received an email from Kaoru Kumi, a freelance writer in Japan who had read the coverage of my blog post translations of Kentaro Takekuma’s lectures (1, 2), offering the opportunity to translate portions of the anime scholar’s extensive book on Hayao Miyazaki, Miyazaki Hayao no Jidai (The Age of Hayao Miyazaki), written in the school lecture style, that contained Kumi’s own in-depth analysis of the Nausicaa manga as well as an engrossing examination of a often-used but rarely-explained term used to describe manga.

Since I’ve been busy as of late, I received Kumi-san’s permission to split the translation duties with SDS of Ogiue Maniax, where the second half of this translation will be posted.

I’ve tried my best to keep formatting simple, with underline used for titles, italics used for unusual Japanese words that were kept untranslated, and (Firstname) (Lastname) for Japanese names. I’d like to thank Kumi-san for giving me this opportunity and working with me throughout the translation process. Also, if you have any comments or questions, as always, please let me know.

Here we go, boys and girls. (laughter) Today, I’ll be talking about my analysis of the Nausicaa manga. Not the movie, the manga. The manga was a long-running series, brought into the world in January 1982, and completed in ’94. I’ve already discussed why Miyazaki started working on this project, so I can skip talking about that today… Or so I’d like to, but if I did, I’d surely see some confused faces, so I’ll tell you about his career as a manga artist before Nausicaa.

As I mentioned earlier, Miyazaki wanted to be a manga creator when he was in his teens. There’s an interview with him where he reflects on that period of his life, and I encourage anyone interested to find a copy of it (( “Kaze no Kaeru Basho” (The Place Where the Wind Returns), interview by Youichi Shibuya for rockin’on)) . Miyazaki has a number of pleasant anecdotes about this period; when he was a senior high school student, he was shocked when told that his own designs and stories were copycats of Tezuka’s manga, and so he burned all his manuscripts, or about the only time during university he brought his manuscripts to a tiny publisher, but was too shy and nervous to ask them to comment on his manga. He says that he had hardly opened the door before he had left the office. His talent bloomed while at Toei Doga, after graduating from university, in the latter half of the ’60s, during which time he published two obscure manga works while he also lead a busy life as an talented animator. The first is Sabaku no Tami (The Desert Tribe), a manga–or more accurately, an illustrated story ((E-monogatari/絵物語))–serialized in Shonen Shojo Shinbun, a weekly children’s newspaper, ((Launched in December 1968 as 少年少女ã—ã‚“ã¶ã‚“, published weekly. Changed its name in March 1970 to 少年少女新èž. Ceased publication in March 2004.)) after he worked hard on Toei’s animated feature The Adventures of Horus: the Prince of the Sun was completed in 1968. ((The title ran from September 1969 to March 1970 under the pen name Saburo Akitsu)) I’ve come across this work on the internet once, and what struck me was how cinematic its image composition is. The story is kind of like if the Pejite tribe from Nausicaa became its main characters. The serialization was cut short mid-run, and the work has never been republished, meaning that the title remains a very rare one. The other work is his manga adaptation of Animal Treasure Island. Only a bit of this was available in a book, and furthermore I was only able to look over it briefly, but this too struck me really as a manga movie. He left Toei Doga after this period.

This was the only experience he had with creating manga up to 1982. Finding out that Animage wanted to have him draw a long series must have troubled him somewhat. There are stories of him repeating many times, “Hmm, I still haven’t got the knack of the syntax of manga” as he was drawing the first chapters. In fact, he would say that he was not sure he was able to draw manga fully with pens. You know, animators use pencils when doing line drawings, right? Being so used to working with pencils meant that he didn’t know how to fully use G pens or ball pens. During its early chapters, except for chapter one, there are actual instances of him using a pencil to draw the manga. Of course, this is while he was working on the television series Sherlock Hound (1982), meaning that he was very short on time, forcing him to submit his completed pages in pencil, not having used pen and ink. Once he left the production team of Hound, he returned to using a pen.

In Hayao no Shigoto, I did an analysis of the Nausicaa manga which garnered quite a response from my readers, but I’m actually not satisfied with my analysis. I mean, while I did tackle the composition of the story, I didn’t tackle any sort of visual analysis from a technical point of view. While manga criticism was once focused just on themes and ideology of the narrative, a form of criticism which adds to that approach by looking at the actual lines on the paper to understand the author’s thought process and the manga as pure image has come to the forefront since the ’90s in the Japanese manga criticism community. You all must know the television program Manga Yawa, on NHK sattelite? On the show, Professor Natsume has a segment where he does manga analysis called “Natsume no Me” (Natsume’s Eyes). Analysis like what he does. I’d been thinking for a while, “I wonder if he’ll ever do Nausicaa…” Incidentally, he still hasn’t done a segment on Nausicaa. Allegedly, Miyazaki won’t OK it. What a narrow-minded man! (laughter) Well fine, if the NHK won’t do it, I will! And with that, I’d like to talk about my technical analysis of the Nausicaa manga.

As soon as the serialization of Nausicaa began, manga lovers began to praise it highly. It seems like the two things you heard the most about it were “it’s quite cinematic” and “its style is dense and hard to read.” This is the opinion of someone who read the manga before watching the movie, and I felt the same way when I read the manga for the first time after seeing the movie.

Putting that aside, what exactly does “cinematic” mean, anyway? You heard the same term applied to another work that began during this period, Katsuhiro Otomo’s AKIRA, even praised as such by the man first said to create “cinematic manga†in Japan, Osamu Tezuka–though in the last 10 years of research, talented scholars have made discoveries leading manga critics to conclude with certainty that “cinematic†techniques were being used in manga before Tezuka began creating cinematic manga. But what does “cinematic” mean? You can’t pin it down. While there are a number of definitions given by a host of manga researchers, none of them sit well with me. To put it bluntly, they’re all functionally useless definitions. Well, there are some ones which are specific and pointed, but there’s always something wrong with them. “What exactly makes a manga ‘cinematic’?” I’ve always suspected that the text that can answer this question is Nausicaa. So finally, I’ve found a way to bring the answer to you, today through my technical analysis of this superheavyweight title. How smart I am, huh? (laughter) Today will be the first time that I reveal this method of analysis in public, so prepare yourselves.

While we use the term “cinematic” a lot, I’d like to pay attention today to the way that shots are connected to other shots. You understand what I mean? I’ve brought a DVD of 2001: A Space Odyssey ((Directed by Stanley Kubrick, produced in America in 1968 by MGM. Often praised as the pinnacle of the sci-fi genre, but Miyazaki apparently hates it.)) with me today, so I’ll explain while we watch. Why did I choose 2001 as a sample? I found the DVD on a shelf in my house. That’s all. (laughter) Just one film has hundreds and hundreds of shots joined together. (DVD begins to play) Those apes grunting on the screens are the ancestors of mankind; they’re picking grass and eating it. While this is all one shot up to here–there, we just cut to another shot, and we see another ape. We can call the filmed shots that’re tied together by an editor “edits.”

There’s four typical patterns of edits. Pattern A: Despite going from one shot to the next, the action continues to take place in the same location, and the subjects remain in the frame, allowing the action to continue uninterrupted.

The astronaut is in the Space Pod hangar, and is about to ride a pod to go out to repair an important device of the antenna on his spacecraft Discovery (1). Look closely at the way his body moves. Even as we go from one shot to the next (2), his movements continue, totally uninterrupted. Ah, a light has turned on in the Space Pod, and something has started whirring as it moves (2′). While there’s an edit between the two shots (2′ and 3), the actors and props on screen remain the same between the two, and they continue to move in the same way, uninterrupted. This is the essential part of this kind of edit. If you still don’t comprehend what I mean, imagine a television broadcast of a baseball game. When you hear the crack of someone hitting a home run, a number of TV cameras all follow the ball. You watch the flying ball from multiple camera perspectives continuously, or uninterruptedly, on the screen. That is a typical A.

Patttern B: The setting drastically changes from one shot to the next, but the characters on screen are in both shots, and are not seen briefly during the sequence.

This takes place inside the space station. The man is using his voice to identify himself. Once the identification takes place, the two take their leave (1), but before they exit from the screen, there is an edit to 2. Now we’re in the space station lobby (2), see? We see the two men entering on screen a split-second after shot 1 cuts to shot 2. In shot 1, the two are passing through space customs, and in shot 2, we’re inside the space station lobby, a completely different location. The essential part of this pattern is that when we cut from one location to the next, the actors don’t appear in both in a continuous way; we do not see them on the screen for a second at the end of shot 1 or at the outset of shot 2. ((Strictly speaking, this can be divided into three patterns: exit from shot A, then cut to shot B, enter to shot B before exiting from shot A (what happens in this case), and exit from shot A, then enter to shot B. Each has their own subtle difference.))

Since the actors are unseen for a moment on the screen in pattern B, then naturally, the action is also interrupted. These men take their leave once they confirm their identities. Before the two can exit from the frame (1), there is an edit, and then they exit by walking out into the space station lobby (2). This sequence occurs in a few seconds, while the actual time to travel that far would be in the tens of seconds. Strictly speaking, we would say that the action is not continuous. However, if we look at it as movement from place X to place Y, the action is continuous in a broader sense of ‘walking from customs to the lobby’. I’ll discuss this later; this is a major point.

Pattern C: The film moves from one location and one set of characters to another location and another set of characters, turning into a separate sequence. They’re having a meeting at the moon base(1). And now we cut, and there’s the surface of the moon (2). A Moonbus is flying above the moon’s surface. The shot of the meeting and the shot of the moon take place in different places and times. Basically, it changes to a different scene. In a novel, this would be a paragraph break.

Pattern D: An edit from one place and cast to another, then a return to the original setting and characters, used to skip the passage of time.

The Space Pod is slowly moving through space (1). Then we cut to a close-up of the antenna (2). When we cut back to the Space Pod, we find it on standby near the antenna (3). In other words, the time in between shots 1 and 3 has been omitted. It would probably take a number of minutes for the ship to arrive at the antenna, but thanks to editing, it only takes a few seconds. It doesn’t feel like anything’s been abridged, though, does it?

These are the four typical ways in which edits are arranged. While we are so accustomed with television and movies that we don’t even notice them, these four patterns are used in almost everything from films to TV dramas. Of course, there are plenty of deviations from these patterns. Even in this film, 2001, there are sequences edited in totally experimental ways towards the end of the movie. But what I want to get across to you is that these 4 patterns are the most basic, fundamental ones there are.

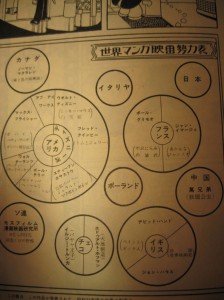

Now, let’s move to the world of manga. Japanese manga is often called “cinematic,” so if that’s really true, we should expect them to be based around the four patterns above. But what’s the actual state of affairs? Let’s take a look.

Let’s start with pattern A.

Azumanga Daioh (Kiyohiko Azuma/Media Works) p.46

(Panel 2: Snap! (ã±ãã£ï¼‰ / Panel 3: “Hehee…” (ã¸ã¸ãƒ¼)/ Panel 4: “Hm?” (ん?) “Hehee…” (ã¸ã¸ãƒ¼) “Is she that happy just because she split her chopsticks cleanly?” (ãã‚Œã„ã«å‰²ã‚ŒãŸã®ãŒå¬‰ã—ã„ã®ã‹ãªâ€¦)

This is Azumanga Daioh. A high school girl nicknamed “Osaka-san” is splitting apart disposable chopsticks. (2). In panel 3, Osaka-san turns to face the tiny girl. ((Try covering up the “Snap!(ã±ã)” sound effect in panel 2, along with the lines to the left of it, then read the comic again. This places the panel into the moment after the chopsticks are broken, rather than as the chopsticks are being broken, increasing the number of actions that take place between panels 1 and 2. In other words, an action is omitted, and turns a A’ edit into a A”.)) In other words, there’s nothing omitted between panels 2 and 3. In panel 4, she’s swung around to show the girl wearing glasses how smartly she split her chopsticks. Again, there’s nothing left out between panels 3 and 4. Because manga is a medium of drawings printed on a piece of paper, we don’t actually see Osaka move, but we use our imaginations to fill in the gaps as she turns left and right. In short, this can be compared to the film pattern A. I’ll call this pattern A’ (A-dash).

There’s one more pattern, A” (double-dash).

Azumanga Daioh (Kiyohiko Azuma/Media Works) p.119

Panel 1: Bam! (ã°ãŸ) / Panel 2: “Let’s get ourselves back together and start yelling in time!” (ã‹ã‘声ã‹ã‘ã¦ãŠã¡ã¤ã‘ã¾ã—ょã†ï¼) “That’s right, let’s take our time.” (ãã‚„ãªã€€ã‚†ã£ãり) / Panel 3: “One” (ã„ã¡) Bam!

Chiyo-chan and Osaka-san are running a three-legged race in the school sports festival. These two are well known for their rivalry, competing for the position of most and second most uncoordiated student at the school (laughter), and from the moment the race begins, they seem to be off to a good start, falling over right there. They encourage each other in panel 2, then fall over again in panel 3 (laughter). While I imagine that this sequence of panels reads quite naturally, if you think about it, there’s quite a bit cut out between each panel. I mean, you try it yourselves. After panel 2, the two have to slowly get back up, then try to start running again, then fall over again, as seen in panel 3. That means that there’d normally be two more actions in between panels 2 and 3, and they’ve been omitted. But, you can read the strip without thinking that anything is strange. ((Try covering up the “One (ã„ã¡)” on the right part of the final panel with your finger and read the strip again. The transition from panel 2 to panel 3 feels abrupt, now. The action, “the girls begin running” is replaced by the “One.” On the other hand, if you cover up the “Hehe (ã¸ã¸ãƒ¼ãƒ¼)” and the curved lines in the third panel (The “keiyu,” or the lines that show that Osaka-san is turning around) of the strip above, it doesn’t seem abrupt at all. This means that in the case of the three-legged race strip, we’re dealing with an A” edit (one or more actions are omitted between the two panels) and in the chopsticks strip, it’s an A’ edit (no action is omitted).))

I’m going to say that these correspond to film pattern A, and if there’s no action omitted between panel and panel, I’ll call it A’, while A” will be if there’s one action or more omitted between the panels. Got that? I’ll repeat it again, don’t make understanding these two a mental exercise, actually use your body to confirm what’s going on. If you do, then that will make things much easier to grasp.

What about pattern B? This would seem to be fundamentally impossible in manga. Take this for example.

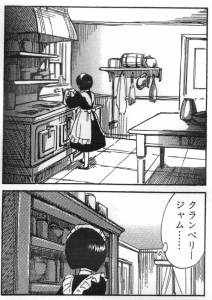

Shirley (Kaoru Mori/Enterbrain) p.98

From Shirley. A little maid is preparing tea in the kitchen. Panel 2 takes place in the same room as panel 1, but her surroundings are different. So in a film, we wouldn’t see her in panel 2 at first, and after a few moments, she would enter the frame. ((In film, there are other edits possible, such as her exiting from the first panel, then already being present once the shot of the new panel starts, or her exiting the first panel, then the second scene appearing, which she proceeds to enter. However, these all have slightly different effects than the setup that I’m hypothesizing. Use your finger to cover the characters up and try for yourself.)) This girl is actually looking for cranberry jam, and so is moving from one shelf to the next in these panels. ((Pay close attention to panel 2, where the line “Cranberry jam…” appears, along with Shirley’s slightly urgent, excited posture. This is what silently helps to support the B’ edit.)) However, in manga, we can only simulate entering and exiting a frame, as these are static images. The reader must figure out what’s going on in these two panels and connect the action internally. Let’s call this B’.

B’ has a relative, which we can see here. (Shown on the screen)

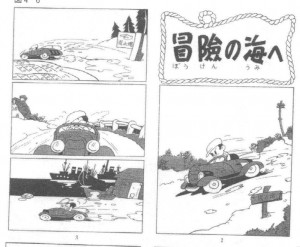

Shin Takarajima (reprinted in Go Itoh,Tezuka is Dead, NTT Publishing.)

This is the beginning of Shin Takarajima, the legendary Osamu Tezuka manga that he drew at the age of 19. It seems to have been an extremely shocking manga to its young readers at the time, as they apparently felt that the car seemed to really be moving, despite the manga being static images on a page. While it’s still highly praised to this day, with individuals saying “it’s like watching a movie!” ((Though notice that there are no onomatopoeias or speech balloons.)), if you look at it carefully, this sequence of edits would be very strange if they were filmed. A car appears throughout panels 1 to 4. As I mentioned earlier, if there’s shots edited together where the action takes place in the same location with the same actors appearing in an uninterrupted way, then it would be pattern A. But as we go from panels 1 to 4, the actors are the same, but the scenery changes. Panel 1 takes place on a downhill road. Panel 2 is in a field. 3 is a road alongside the coast, and 4 is at a harbor. While the character’s action is not interrupted, the scenery is. Generally, films tend to avoid this style of editing. However, in manga, there is nothing strange about this. Consistent action–in this case, furiously driving a car at a high speed–allows the reader to overlook the disconnected flow of scenery. While this is similar to the A’ pattern, the character stays the same on the page while the background changes. If this sequence was to be filmed, I imagine that the character would have to be out of the frame at some point, meaning that it is closer to a B pattern. I’m going to classify this as a B” edit.

While Shin Takarajima is still used today as an example of “cinematic manga,” I wonder if Tezuka actually knew what makes a manga “cinematic.” Tezuka would re-draw the work entirely and publish it once more as the “complete edition” dozens of years after the first edition, and I found it was really unexciting, or not “cinematic.”

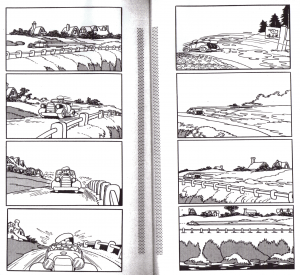

Tezuka Osamu Manga Zenshuban Shin Takarajima (p.10~11)

The new version also begins with a car racing down a road, and for some reason the new edition seems overly stretched out; the revised one is set up as if a camera in a helicopter was constantly tracking the car. While a sequence like this would certainly look cool on TV or in a film, it just drags on when drawn on paper. I imagine that Tezuka, upon drawing this revised edition, thought proudly to himself, “look at how dynamic these pages are!” but I wonder why no one tried to stop him. “Tezuka-Sensei, this just looks like slow motion.” ((According to Tezuka, the panels that you see in the revised edition were ones that he wanted to draw from the beginning. If this is true, that means that his co-author on Shin Takarajima, Shichima Sakai, decided upon the original layout. So the B” edit was first invented by accident…? I wonder.))

I’ll be calling the kind of pattern seen in the revised edition of Shin Takarajima B”-(double dash minus), and I’d like to look at another example to illustrate my point.

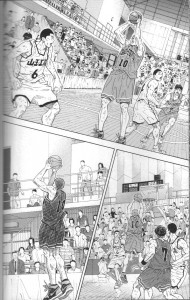

Slam Dunk, Jump Comics Deluxe volume 24 (Takehiko Inoue / Shueisha) p.208

One second left in the game and Sakuragi-kun goes for a game-winning shot! We see multiple panels with the same character in the same location, but with different composition in each panel. At a glance, it might remind you of the opening sequence from the revised edition of Shin Takarajima, but in fact these three panels are drawn from entirely different perspectives while the panels from the revised Shin Takarajima are from a single perspective. In other words, it is like how multiple cameras might follow the same home run ball during the broadcast of a baseball game. I.e., this is A’. But it looks like a B”-, doesn’t it? ((In a B” sequence, the characters are the same, but the time and place between each panel are disconnected from each other. The B”- sequence is comparable to a long take in film.)) The strong point of the A’ shot is its dynamism, while for B”- it is its slow motion effect. This A’ sample is impressive for deftly blending A’ and B”- effects, creating a very dramatic scene, one 1/10th second at a time. ((I’d like to sit down and analyze Slam Dunk one day.))

Pattern C is fairly common in manga, right?

Whisper of the Heart (Aoi Hiiragi / Shueisha) p.81

This is the original Whisper of the Heart. Shizuku-chan and Seiji-kun are quarreling for some reason in the library. Her father, a librarian, also appears here. After that, we see the image of falling rain, introducing a whole new scene. I’ll call this pattern C’. There are other, more subtle ways of changing scene and setting.

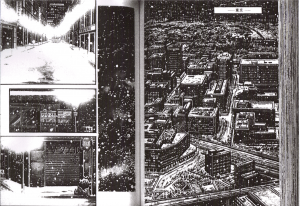

SP Comics Compact Golgo 13 volume 57 (Takao Saito, Reed-sha) p.170-171

From Golgo 13. We see the streets of Tokyo via a series of panels. No one panel is directly related to the next, as their main purpose is to express the feeling of the city itself. We see this technique used in films quite a bit, don’t we? I’ll call this pattern C”.

As far as pattern D, we see this quite often in manga.

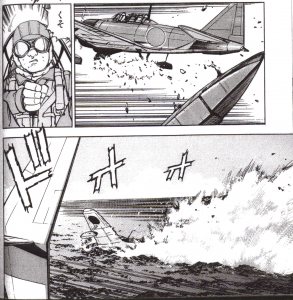

Zipang 2 (Kaiji Kawaguchi/Kodansha) p.82

This is from a war manga called Zipang. It’s a SF-ish story about a state of the art Japan Self-Defense Force ship, getting sucked in by a storm and being spit out right in the middle of World War II. Here, a JSDF propeller plane is out on a scouting mission, is found by a Japanese Zero Fighter, and gets into a dogfight. Forced to counter fire, the JSDF plane shoots at the Zero in panel 1, aiming at the float attached to the bottom of the plane. Panel 2 is a closeup of the Zero’s pilot. In panel 3, the Zero makes an emergency landing in the ocean, or rather, he crashes into it. For your information, the thing you see in the left side of panel 3 is the JSDF plane’s wing. While I believe that a dozen seconds or so must take place in this sequence, we get a closeup of the pilot in panel 2, allowing the time between panels 1 and 3 to be shortened considerably in a clever way, resulting in a crisp and exciting battle scene. This definitely corresponds to pattern D in film, so I’ll call it pattern D’.

Manga are still images, drawn on pieces of paper. Even so, I bet you often think “wow, this seems just like I’m watching a movie,” don’t you? Take this, for example.

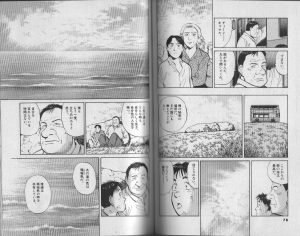

Master Keaton 7 (Story: Hokusei Katsushika, Art: Naoki Urasawa/Shogakukan) p.78-79

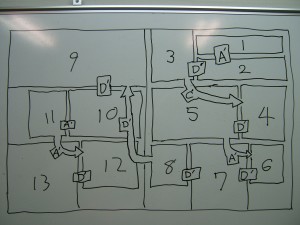

This is Master Keaton. I happened to find that a talented manga researcher singled out these two pages in one of his books, and indeed these pages are really incredibly “cinematic.” Yes, I agree that they’re cinematic. However, I’m a bit disappointed that this researcher never grappled with the question of what makes these pages “cinematic.” ((Tezuka is Dead, Go Itou, NTT Publishing. While it is an excellent work, I found it very strange that he discusses “cinematic techniques” at length but never gives a definition for this term, nor is this term found in the index.)) I then took it upon myself to analyze this page, and noticed that this page of this manga consists of nearly all A’ and D’ patterns. If we map out the panels and write out each editing pattern… (written on whiteboard)

See what I mean? These pages go A’, D’, C’, D’, A’, D’, D’, (new page) D’, D’, A’, A’, D, and are extremely readable. When I say that these pages are nearly all A’ and D’, it also means that there are absolutely no instances of A” patterns.

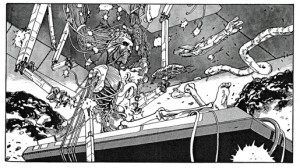

So what about the Nausicaa manga? Surprisingly enough, we find quite a few A” patterns used. Strangely, though, it never feels very noticeable. I found this one particularly impressive.

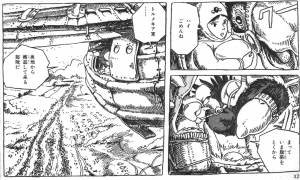

This is a scene where Ketcha is returning Kui’s egg. This happens to take place inside a transport glider. In panel 2, Ketcha is seen trying to loosen Kui’s saddle. A sequence of panels that has the same characters in the same spot, performing an uninterrupted action is the typical A pattern that we discussed earlier. However, if you really pay attention here, you notice that Ketcha’s actions aren’t uninterrupted. In panel 1, she is holding a giant egg, but in 2, the egg is already under Kui’s thighs. That means that the two actions, bending over and placing the egg, then standing up (The lecturer acts the scene out in front of the students) have already taken place, meaning that actions have been omitted between 1 and 2. ((However, due to the dialogue, “Oh, sorry.” “Wait, I’m taking off the saddle.” being continuous, this sequence flows naturally.))

Furthermore, in panel 3, Ketcha’s head is poking out of the window of the glider as she looks at the ground below her with Yupa. I believe that the edit from panels 2 to 3 corresponds to the film pattern B. If this were a film, we’d first see just Yupa’s head looking out the window, then Ketcha coming to poke her head out afterward. Actually, if I was adapting this manga into a film, I’d add one shot in between 2 and 3. Once Ketcha finishes unfastening the saddle in 2, the shot would change to something like this. (board drawing)

Then we’d cut again to panel 3.

Why do you need to insert another shot into the sequence when you adapt it into a film, unless you see Kecha trying to poke her head in the cut equivalent to panel 3? It’s because the subject’s action has to be continuous in a broader sense even if it is actually being interrupted for a second on screen. In a film, going straight from taking off the saddle (2) to looking out the window (3) would seem far too rushed and disconnected. But, if we have her join Yupa looking down from the window, we know it’s because time has elapsed and she’s finished taking the saddle off. Since there’s no sense of continuous action from panels 2 to 3, this wouldn’t be a B pattern even when you put this sequence faithfully into film form. Again, I would probably insert the extra shot between panels 2 and 3 to make the sequence a D pattern rather than a B when adapting the work to film syntax. ((Actually, I can think of one other way of doing this, with Ketcha leaving to go to the window as Kui goes to sit back down on her egg (exiting the frame here would not be needed but is preferable). As soon as this happens, we’d cut from 2 to 3, then Ketcha enters the frame (we see her peek out from the window). The only problem here is that you’d have to animate Kui sitting and Ketcha going to the window (at the same time, at that!), which would require extra labor.))

Oh, sorry, I’m going off on a tangent about film editing, rather than manga, so I’ll try to get back on track. Assuming that this sequence is a B’, I can’t say it perfectly meets the requirement that in a B’ edit the subject’s action has to be continuous in a broader sense even if it is being interrupted for a second when a shot cuts to another. But, in fact, this sequence is quite easy to follow. If you’re wondering why, look at it more closely. Panels 1 and 2 take up the right side of the page, while panel 3 takes up the left side. This page almost reads like a map of the inside of the glider. Did you love illustrated encyclopedias when you were a kid, everyone? They often map out how each section or room is laid out inside a ship or a house in a single illustration. I think Miyazaki applied this style to the visual composition of this sequence–maybe unconsciously. We can see traces of Miyazaki’s childhood love of illustrated encyclopedias in this page.

Let’s go back and compare it to the Master Keaton we just looked at. Theoretically, we would say that Keaton, which uses no A” edits, would be more cinematic than Nausicaa. However, if we look at the two side-by-side, Nausicaa seems no less cinematic than Keaton. Why? Look closely. Many panels in Keaton extend beyond the page. We see this four times in these two pages. On the other hand, this very rarely happens in the Nausicaa pages. Incredibly, there are only two instances in the entire run of the Nausicaa manga where panels are not box-shaped. No matter how incredibly complicated and crowded the art gets, it’s always contained in rectangular panels. For a modern manga, this is a fairly rare, or should I say abstemious, spartan work.

There’s another reason that the Nausicaa manga is cinematic. During action scenes, quite a few of the edits are A’s. Take this for example.

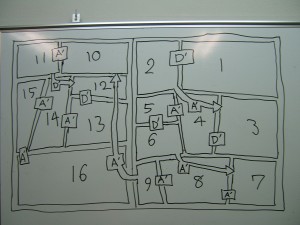

A fighter plane from the Valley of the Wind meets a Tolmekian warplane, and they get into a dogfight. Breaking down these panels, we get D’, A’, D’, A’, D’, A’, A’, A’, (next page) A’, A’, D’, D’, A’, A’, A’. Now this is incredible. A’ edits, full throttle! ((Panel 1 to 2, where the focus of the panel goes from the Valley of the Wind fighter to the Tolmekian warplane might seem like a D’, but if we consider the bullets as the focus, then this would be an A’ in substance. 3 to 4 and 5 to 6 would be similar. 11 to 12 and 12 to 13 are D’s, but if we consider the pilot as a part of the airplane, then these too would become A’s.)) The quick speed at which the reader goes through these panels matches the speed of the action. Furthermore, look at panels 11 and 12. Panel 11 is what Asbel, seen in panel 12, is seeing. Manga researchers call this technique “character-reader unification.” 11 and 13 have fundamentally the same composition, but strictly speaking the camera is behind the fighter plane in the latter panel while the former panel is drawn from the pilot’s perspective. Since the enemy plane is larger in 13 than it is in 11, we feel like the plane is quickly closing in. Also, supposing that Miyazaki redrew panels 11 and 13 both from the pilot’s perspective or from that of the imaginary camera following the plane in a high speed dive, skipping panel 12, this sequence would still work fine, but it would certainly lose its exciting dynamism since it turns into a B”-, or into slow motion. By inserting Asbel’s face between panels 11 and 13, and also changing the camera perspective, Miyazaki escapes creating a drawn-out scene that B”- sequences tend to create.

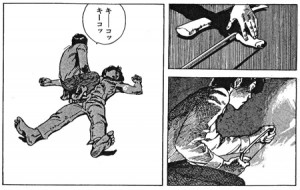

Let me bring out another example. This one’s from Zipang:

Zipang 2 (Kaiji Kawaguchi/Kodansha) p.60

A Zero fighter begins firing on a JSDF plane. If we break down the panels, we get D’, D’, A’, D’. Kawaguchi’s manga, such as Zipang and The Silent Service, are often praised as “cinematic.” However, we see surprisingly few A’ edits here. The reason behind this comes from the time schedule that this work is produced on. Nausicaa wasn’t serialized in a manga magazine, but rather an anime news and information magazine. That meant that the manga could be produced very slowly, around only 16 pages a month. Compared to that, Zipang was serialized in the weekly magazine Morning, which would call for 18 pages a week. Of course, this kind of volume can’t be produced by one person alone, and so Kawaguchi-sensei has 6 to 7 assistants in his studio, all working together to produce the manga. The basic sketches of the panel layout and composition, what Japanese manga artists normally call “Name”s, are created by Kawaguchi, who would also draw the main characters such as the pilots. However, things like the Zero and the JSDF plane, or the spray of the waves of the ocean would be handled by his capable assistants, using photos as reference. To make a grossly simplified classification, there are two kinds of panels here: ones that Kawaguchi penned himself, and ones that were only laid out by him that the assistants would work on, both of which would appear normally next to each other in the manga. Naturally, there will be more D’ edits.

So, in both Nausicaa and Zipang, we see panels of a pilot’s face inserted in the dogfight scene. But in the Nausicaa example, doesn’t it feel like the pilot is actually a part of the plane, or rather, that the plane is an extension of the pilot? While we are shown the faces of a given plane’s pilot, whether that is Asbel or Mito or a Tolmekian soldier, it ultimately feels like we’re watching two birds engaged in aerial combat. In Zipang‘s case, the JSDF plane and the Zero both seem like plain machines, and it feels more like the pilots are the main characters of the scene.

However, the techniques that these two have in common are their use of on’yu (sound effect, or “sonopher”) and keiyu (visual effect, or “formpher”). The “DAKAKAKA (ダカカカ)” and the “VUII (ヴイイ)” you see in the top and bottom panels are on’yu. We also see some strange, thin lines surrounding the plane. These express that the plane is flying at a high speed, and we call these keiyu. On’yu and keiyu are a vital part of what makes comics, especially Japanese manga, so dynamic. However, you have to be careful not to overuse them, or else they get in the way of the story.

Let me show you an example of these techniques used in an unintrusive way.

Yotsuba&! 1 (Kiyohiko Azuma/Media Works p.118)

From Yotsuba&!. These are succinct and unintrusive. Nonetheless, on’yu and keiyu are being used in a very subtle way. As an experiment, let’s erase the keiyu next to Fuuka-chan’s head and the “Gara (ãŒã‚‰ã£)” on’yu in panel 3.

In the original panel 2, Fuuka-chan is bending her head back when she hears her mother calling, but if we erase the keiyu in the panel, it looks as though she was in that position even before her mother called her. Thus, the relationship between panels 1 and 2 become fuzzier without the keiyu.

Next, panel 3. Here, Fuuka-chan opens the door, “Gara,” and says “what?”, but if we take the “Gara” out, it seems like the door was open before she entered the room, see? To put it a different way, just by using the on’yu “Gara,” the action of “Fuuka opening the door” is expressed–the reader fills in the blank, mentally. While Yotsuba&! seems like a relatively simply drawn manga, it still uses on’yu and keiyu, in subtle ways. In some ways, you could consider this as a very restrained manga. Although, a surprising amount of work went into Fuuka-chan’s chest in panel 2. ((Say that the magazine wasn’t slightly being held slightly above her stomach in panel 2. If that were the case, there’d be no shadow on her stomach, which would mean that her breasts were less emphasized than they are here. I’d also like you to notice that the edge of the spine is close to touching her nipple.)) Azuma-sensei, you perv (lots of laughter).