Japanese Lecture/Blog Post Translation: The Space Between Anime and Manga: #5: Katsuhiro Otomo, the Anti-“Story” Author by Kentaro Takekuma

Quick translator’s/blogger’s introduction, hopefully shorter than the one to the previous translation of the outline for the lecture given before this one, Why is the Manga Version of Nausicaa So Hard to Read by Kentaro Takekuma, best known in America for Even a Monkey can Draw Manga This lecture was originally given at Kyoto Seika University on 2008/12/18, and the blog post of these outlines can be found here and here.

Formatting for this one will probably be a little sloppier since this won’t be used as a translation/writing sample for school, but I’ll do my best to stay consistent with (Firstname) (Lastname) with names, no capitals this time. I don’t really have much else to add to this, other than that hearing this lecture got me to go down to Mandarake and buy up a bunch of Otomo’s short story collections, which were all engrossing.

———-

The Space Between Anime and Manga

Outline for the lecture series given at Kyoto Seika University

#5: Katsuhiro Otomo, the Anti-“Story” Author

Lecturer: Kentaro Takekuma

The State of Manga During the 70s and 80s

Katsuhiro Otomo debuted as an author in the early 1970s. I’d like to begin by trying to give some structure to the state of manga from his debut in the early 1970s to the early 1980s. The manga world during this time was going through an incredible period of change, which we may never see the likes of again. To try to sum it up briefly:

*Gekiga enjoys its period of full maturity thanks to the rise of Seinen magazines (Big Comic, Manga Action, Young Comic, etc)

*Circulation of Shonen Sunday and Shonen Magazine drops severely, due to the oil price shock, seinen magazines attracting their older readers, and emerging shonen magazines such as Shonen Champion, Shonen Jump and others taking their younger readers.

– The next generation of manga magazines begins at this time.

*The shoujo manga boom begins, attracting male readers alongside female.

– Central to this boom were the female authors in the “Year 24 Group” such as Keiko Takemiya-sensei.

*The first Comic Market is held in 1975.

*Magazines targeting a hardcore audience, such as Manga Shonen and Manga Kisoutengai begin to be launched one after the other, starting around 1977. (The anime boom starts during this period, as well.)

These trends in the manga world, from gekiga to shoujo manga, as well as the creation of fan-targeted magazines, which Comiket and the anime boom both tied into, all combined to form a base for the manga and otaku culture we have today.

Katsuhiro Otomo’s Traits as an Illustrator

As he didn’t attract much attention until relatively late in his career, it is often mistakenly thought that Otomo didn’t begin drawing until the end of the 1970s, but in fact, Otomo debuted in 1973. He began submitting works to Shonen Sunday and COM in the early 1970s, and his real debut work was “Juusei” (“Gunshot”), published in the August 1973 issue of Weekly Manga Action Zoukan. In the following years, he published more short works at a leisurely pace, and began to attract attention from other professional manga artists as well as manga fanatics in the mid-1970s.

The reason Otomo didn’t attract much attention at first was a combination of his extremely low output and a popular conception that his stories and art were plain. Of course, even these earliest works are of unusually high quality, clearly displaying his talent while deviating from the trends of mainstream manga of the time. However, Otomo’s scripts during this period very intentionally avoid and reject climaxes, which would understandably cause his works to be buried under the passionate, intense manga that was prevalent during the period.

We can view these early Otomo works, with their subdued art and scripts, as the antithesis to gekiga, which was at the height of its popularity during this time. Though gekiga can be seen as the antithesis to Tezuka-style manga itself, as it attempts to introduce a new level of realism to manga, Otomo’s manga does not attempt to return to a Tezuka-like style. Instead, it inherits the tradition of realistic art that the gekiga movement started, while boldly rejecting the expressionistic techniques that gekiga developed (panel frames extending beyond the page, super-dense motion lines, manga symbols (tl note: manpu, basically the sweatdrops and forehead veins we all know and love), standardized poses during action scenes, and so on).

I imagine that Otomo must have considered the realism of these techniques and concluded that they weren’t realistic at all. By removing all the conventions that readers had come to expect in manga, Otomo achieves his own level of realism, creating a feeling similar to that of, say, the one felt when watching Takeshi Kitano’s early films.

This aim towards realism extends to a large number of Otomo’s early works where he intentionally does not draw “money shots.” Such flashy scenes must have been thought of as unrealistic to him. Looking back on his work from a present-day standpoint, though, it’s shocking to now see how Otomo’s doctrinally anticlimactic output perfectly captured the mood of the 1970s.

If we look at the 60s as a period of politics and rebellion, as symbolized by the student movement, then the 1970s were a period of societal lethargy, born from the stall in the student movement and the end of the post-war economic miracle. Many young men and women during this period not only felt directionless, but had to worry about even having a roof over their heads from day to day. Whether it was Marxism, Free Love, or Indian spiritualism, young peoples’ values seemed to become more self-centered and introverted.

Finding himself in the center of this group, Otomo realistically drew the daily idleness of the lives of high school and college students. While on occasion he dealt with extraordinary themes like violence and rape, he drew these without traditionally-used “money shots” or a general eye towards making his manga as stylish as possible, but rather depicted these events from an extremely objective viewpoint. For example, when someone gets shot in Otomo’s manga, we don’t see the shooter in a generic pose, a closeup of the gun’s barrel, or the moment that the bullet is in flight. Instead, Otomo draws our attention to a man-shaped thing falling to the ground. Instead of drawing a cool, set pose after one person shoots another, Otomo prefers showing the uncertainty and shamefulness of the act, and it is this sort of realism that caused Otomo to go unnoticed and unacclaimed for so long.

Otomo began using a mapping pen fairly early in his career. In gekiga works of the time, characters were drawn with the dynamic lines of a G-pen, and the mapping pen was used in a supplementary fashion, drawing scenery and action lines. However, Otomo drew everything in the thin, lean lines of a mapping pen, giving equal weight to both character and scenery. While this is the source of the sense of objectivity seen in Otomo’s manga, this technique was an unthinkable one in the world of gekiga until this point, as drawing in this manner would normally just elicit the reaction that “the characters don’t stand out.”

While Otomo used a lot of filled inking in his earliest works, the darkness of his earlier works begins to fade as time goes on, and he begins to use large areas of white space in both character and setting shots. Again, his panel layout was very orthodox, avoiding overly formal techniques such as extending panel frames to beyond the page, and he used very few manpu. We could say that the defining characteristic of Otomo’s work during this period is that it was “anti-manga style,” and was instead similar to the real-life image.

It’s been said that Otomo’s 1970s manga were the first time that a Japanese person was drawn with an Asian face in manga. (“Okasu”, 1976)

It’s been said that Otomo’s 1970s manga were the first time that a Japanese person was drawn with an Asian face in manga. (“Okasu”, 1976)

One could say that another one of Otomo’s “inventions” was his way of depicting Japanese characters with Asian facial characteristics, such as almond-shaped eyes and a low nose. For example, in Takao Saito’s manga, a character like Golgo may be Asian according to the story, but looks nothing like an Asian man. Again, Otomo’s blunt objectivity brought about a new kind of realism to an aspect of manga that had previously been dominated by manga’s “lie” of characters depicted in a borderless way. This too is a kind of realism that could only have been established in the 70s.

The “Anti-Story” Seen in “NOTHING WILL BE AS IT WAS”

I’d like to present Otomo’s 1977 “NOTHING WILL BE AS IT WAS” as good example of a work that exhibits the defining characteristics of 70’s Otomo. This work is about a man who, after unthinkingly killing his friend during an argument in his room, is faced with the problem of disposing of his friend’s corpse, followed by his eventual dismembering and “disposal” of the body.

This work completely does without aspects of a murder case that a criminal drama would depict, such as the killer’s motive or methods. In the very first panel of the story, we see a closeup of a dead body lying on the floor of an apartment room, and from there all we see is the main character’s disposal of his friend’s corpse in a detailed but disinterested way. In the end, we don’t even see the consequences of the crime. The only thing we do see is the main character’s neighbors thinking that he’s acting suspicious, but not a single thing about the discovery of the crime or the character’s arrest.

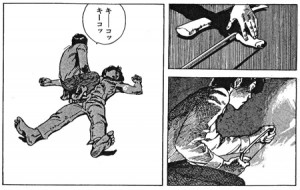

“NOTHING WILL BE AS IT WAS”, from 1977. Unable to cut through fat, the main character has to keep heating his hand saw in order to dismember his friend. This seems so real you might begin to wonder if the author has had experience killing a man himself.

“NOTHING WILL BE AS IT WAS”, from 1977. Unable to cut through fat, the main character has to keep heating his hand saw in order to dismember his friend. This seems so real you might begin to wonder if the author has had experience killing a man himself.

In other words, this work is like a simulation of what a person would do if they had inadvertently killed a person in their apartment. Otomo simply wanted to depict the difficulty in dismembering a corpse in one’s own apartment, and ethical themes such as how the murder came to happen, the protagonist’s feelings of guilt, or the main character’s fate after his crime is discovered are completely absent. The author simply does not seem interested in “typical stories” like that.

We can also see Otomo’s “anti-story tendencies” in the irregularities of the story in works such as his 1976 “Okasu” or the 1977 “Uchuu Patrol Shigema”. While the plots of these works would normally not be enough to base a manga on, Otomo’s artistic and directorial skills, based upon his thorough devotion to realism, make these works possible.

Otomo in the 1970s was able to use his exceptional artistic talent to demolish the idea of the “story”. By bringing his story down to the same level as his art, any sort of moral messages could be excluded. This could be called the defining element of the early Otomo’s style of realism.

Turning the “background” into the main character

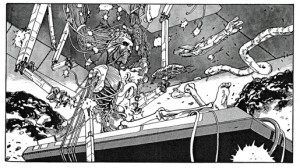

The incredibly famous scene from “Fire Ball” (1979), where the main character, reduced to bones and organs, rises from the operating table. This one nightmarish panel fixed the path for all of Otomo’s later works.

The incredibly famous scene from “Fire Ball” (1979), where the main character, reduced to bones and organs, rises from the operating table. This one nightmarish panel fixed the path for all of Otomo’s later works.

Katsuhiro Otomo first gained public attention after the publication of his 1979 “Fire Ball.” This is the work where Otomo’s sci-fi side, which could only be seen in small glimpses in his previous short works, came into maturity. It was also the prototype for his later work AKIRA. The protagonists of the story are a pair of brothers living in a future world controlled by a computer. While each were living their own separate lives, the older brother a policeman and the younger brother an anti-establishment activist, the giant, society-domineering computer discovers that the older brother has psychic talents, and vivisects him for research purposes. Meanwhile, the younger brother attempts to destroy the computer, but is discovered shortly before he is able to, and is shot to death. At that moment, he telepathically calls out to his older brother, who is then being analyzed by the computer, causing his psychic abilities to manifest themselves. He rises off of the table, his body nothing but bones and organs, and begins to use his terrifyingly incredible powers to destroy the city.

The surreal image of the older brother rising from the operating table was sensual and overwhelming, and coupled with his outstanding art, was the topic of much discussion at the time. This work also marks the moment that Otomo, who had previously intentionally avoided climaxes, created a work with a flashy climax, and the mix of objectivity and visual flashiness that Otomo realized in this work was perfected in his later works such as Kibun wa Mou Sensou (written by Yahagi Toshihiko) and Domu.

While the plot of “Domu”, a work where a senile man and young girl have a psychic battle set in an enormous apartment complex, is certainly a unique one, Otomo’s successful depiction of the innate strange eeriness of the work’s urban setting is what elevates it to a masterpiece of modern horror. The inorganic way in which each individual within the apartments is implanted inside it is perfectly matched to Otomo’s objective style, and it could even be said that the real main character of this work is the apartment complex itself. Otomo’s manga gives its characters and its backgrounds equal prominence, and with Domu he successfully created an exceptionally unique work within manga where background (the scenery) is given the lead role. This style comes into full bloom in his later work AKIRA.

AKIRA, which began serialization in Young Magazine in 1982, along with its anime adaptation, brought worldwide fame to Otomo.

Katsuhiro Otomo, the Filmmaker

Looking at Otomo’s work through the lens of manga history, his works could be seen as ones which exemplify one style of “film-like manga”. (it could also be said that while his literary style differs from Tezuka’s, Otomo’s made a return to Tezuka’s cinematic style in other ways) His extreme attention to the “objectivity” of his drawings led to the restrained uniformity of the thickness of his pen strokes and the exclusion of mangaesque techniques such as manpu wherever possible. However, he ultimately expresses and treats time in paper 2d media in a very manga-like way.

You can get a good idea of Otomo’s orientation towards live action film in a manga such as “San Bergs Hill no Omoide”. In the work’s climactic shootout, you may be reminded of the action direction of one of Otomo’s favorite directors, Sam Peckinpah. Peckinpah’s frequent usage of many quick cuts, as well as slow motion during important scenes, can be seen beautifully expressed in Otomo’s onomatopoeia-free pages full of many small panels. Of course, while this technique is cinematic in a way, it is at the same time something that could only be expressed through manga. If you get a chance, compare this work to Peckinpah’s masterpiece The Wild Bunch. I think you’ll find it very interesting.

Eventually, the cinematically-inclined Otomo was naturally steered towards creating films himself. As a long-time movie fan, Otomo had made self-produced films since his school years, and had been still creating films such as Jiyuu wo Warera Ni while working as a manga-ka. What finally got him into animation was his being hired as the character designer for Rin Taro’s 1983 Harmageddon, produced by Kadokawa Pictures.

Otomo’s work on this movie stretched far beyond his given position of character designer, as he became a major contributor to many sides of the film’s production, submitting setting concept art and imageboards. He was also able to meet many talented staff while working on the film, and thus the door to becoming an anime creator was opened to him. Otomo’s maiden work was “The Order to Stop Construction” (written by Taku Mayumura, 1987), one part of Kadokawa’s omnibus Neo-Tokyo. This work is so incredibly well made that it’s shocking to think that it’s Otomo’s directorial debut. Otomo’s visual technique of the “background as main character” in this work slowly corroding the characters of the anime is perfected in his feature-length AKIRA, a film that stunned both live-action and animation filmmakers around the world.

Otomo has distanced himself from manga in recent years, and has been working primarily as a filmmaker since the late 80s, and while he’s made many exceptional films, I doubt that I’m the only one out there who hopes that Otomo will once again return to making manga.